Five years ago, I fairly confidently stated that Cloud Repatriation Isn’t a Thing, and I by and large stand by what I wrote. That said, it’s 2025, and the story has changed somewhat.

The innovation premium vs. the end of free money

To review, since you probably didn’t click that link: I’ve been saying for a long time that moving to cloud isn’t an endeavor that’s going to save you any money—it’s an innovation play. Being cloud-based lets you iterate very rapidly, and in return it costs a premium to let you do that. Since companies generally don’t hire idiots to their executive suites, the dark art of arithmetic hasn’t passed these people by, and they’ve knowingly made this bargain, and are doing so en masse.

However.

Now that we’re no longer in a zero-interest-rate environment, it’s natural to look at some of those expensive steady-state cloud workloads and begin to wonder. After all, “how to run a fixed number of servers in a data center” isn’t prehistoric knowledge known only to the ancients like how to build a Stonehenge. We know how to do this ourselves, and saying that there’s no economical way to do it unless you’re a hyperscaler is fallacious.

When money was effectively free, the “cloud premium” was easier to justify as the cost of doing business. Now that capital actually costs something again, CFOs are taking a harder look at those monthly AWS bills and asking pointed questions about whether all of that compute really needs to be so flexible—and expensive.

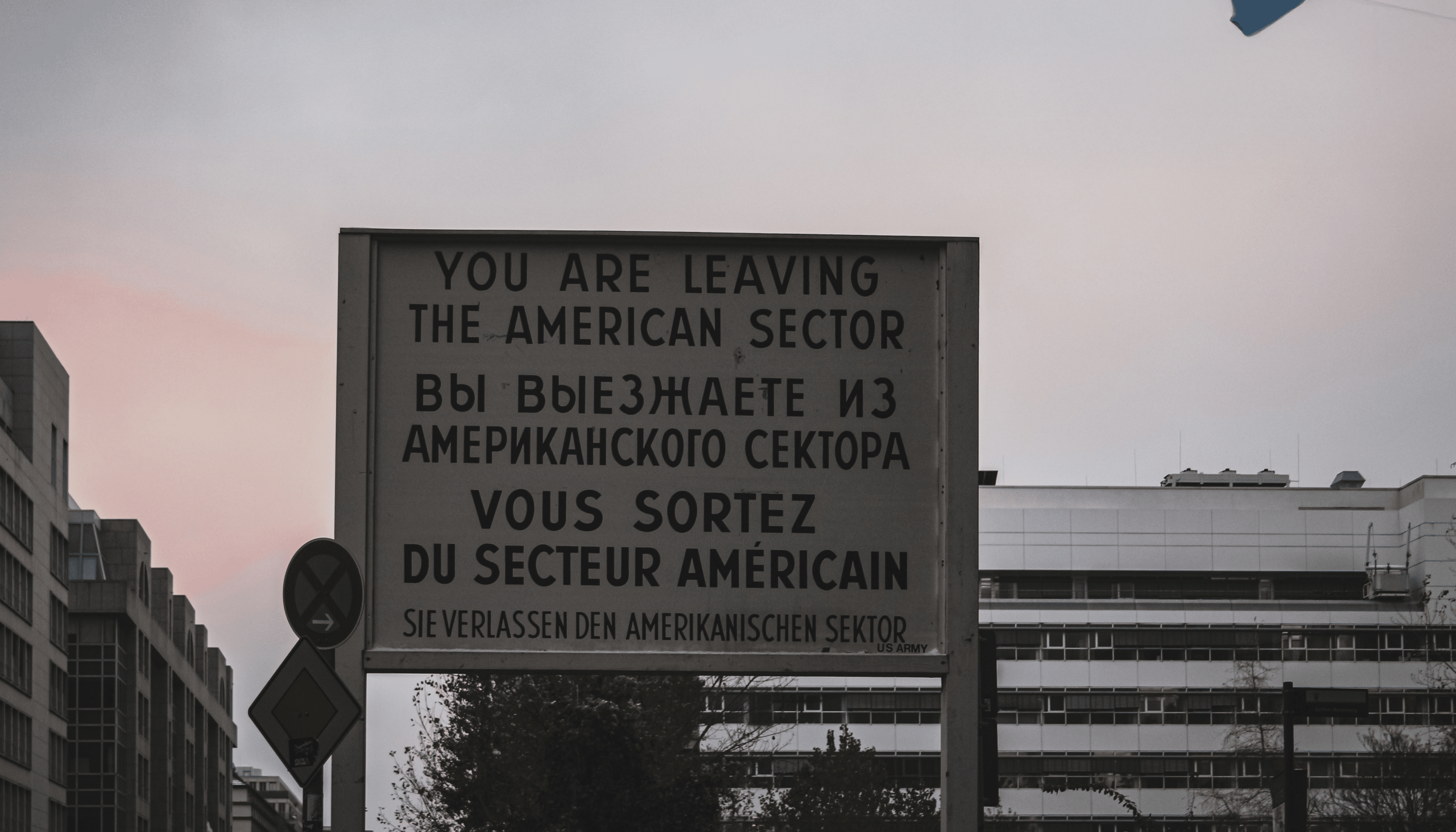

Data sovereignty concerns are real

Add in that companies tend to be global these days, and there is significant concern among their customer bases about the perils of keeping data in US-run cloud providers. Whether those concerns are misplaced or not is entirely beside the point—they’re real to the customer, and thus have to be respected by their vendors.

Who’s talking about this, and why

Here’s where it gets interesting. Workloads and companies that haven’t meaningfully innovated in a very long time are terrific candidates for this kind of repatriation exercise, and they’ll talk about it, a lot, at tremendous volume, because why not? It’s not like they’re meaningfully doing anything else, and attention-based marketing is scarcely a new thing.

The familiar cast of characters is back. The same vendors who’ve been desperately hoping that cloud was just a phase are dusting off their old pitches, and analyst firms are once again telling legacy infrastructure companies exactly what they want to hear. The Dropbox story gets trotted out with religious fervor, conveniently ignoring that they had one very specific, very well-understood workload and you probably are not Dropbox.

It’s fascinating how selective everyone’s memory has become. Remember Zynga? They tried the whole “let’s move out of AWS and run our own data centers” thing, discovered that was a spectacular mistake, and came crawling back to AWS so thoroughly that their return became an AWS case study. Somehow, that story doesn’t make it into the repatriation sales decks. Funny how that works.

Peer pressure isn’t strategy

I don’t know how you folks handle decision making in your environments, but “everyone else is doing this” is seldom a defensible reason for making significant swings in architectural direction—with the sole exception of Kubernetes. Yet here we are, with companies looking at each other sideways and wondering if maybe they should be doing this repatriation thing too, because everyone’s talking about it.

Here’s the thing, though: there’s a world of difference between smart infrastructure decisions and colossal blunders dressed up as strategy.

The real story behind “repatriation”

I’ve seen companies do proper due diligence—like a finance firm I worked with that ran the numbers on HPC workloads and correctly concluded they belonged in their own data center. They never migrated to cloud in the first place because they did the math up front. But that’s not repatriation; that’s just not being an idiot.

Most of what we’re seeing isn’t that. It’s companies that moved some workloads to cloud, realized a handful of them don’t belong there, and are now trying to spin moving those specific workloads back as visionary cost optimization. Let’s be clear: these companies didn’t shut down their data centers and go all-in on cloud in the first place. They kept their infrastructure running, selectively moved some workloads up to the cloud, and now they’re selectively moving some back down to the data center again.

There are hidden costs that they’re not mentioning, but these are not about rebuilding from scratch—they’re about the operational overhead of constantly shuffling workloads around and the complexity tax of running optimization theater instead of just… running a business.

Next stop: hybrid hell

The cherry on top is that once you repatriate some workloads, congratulations—you’re now managing two environments. Because hybrid complexity is exactly what every infrastructure team was missing in their lives.

Hold me to this: in five years, smart companies will still be making smart choices, the usual cloud bears will still be trying to make “repatriation” a thing, and I’ll ship another blog post about the topic. See you there.